This is the third post in the series, this post deals with the systematic interpretation and analysis of X-ray Chest with special emphasis on silhouette sign and hidden areas of the lung.

Whenever you review a chest x-ray, always use a systematic approach.

We use an inside-out approach from central to peripheral.

First the heart figure is evaluated, followed by mediastinum and hili.

Subsequently the lungs, lungborders and finally the chest wall and abdomen are examined.

You have to know the normal anatomy and variants.

Once you see an abnormality use a pattern approach to come up with the most likely diagnosis and differential diagnosis.

It is extremely important to always

compare with old films, as we will demonstrate in this case.

Actually someone said that the most important radiograph is the old film, since it gives you so much information.

For instance a lung mass, which hasn't changed in many years is not a lung cancer.

Actually someone said that the most important radiograph is the old film, since it gives you so much information.

For instance a lung mass, which hasn't changed in many years is not a lung cancer.

First study the chest films.

Then continue.

Then continue.

Based on the CXR that you just saw,

you could have made the diagnosis of congestive heart failure, but the findings

are very subtle.

However once you compare it to the old film, things become more obvious and you will be much more confident in your diagnosis:

However once you compare it to the old film, things become more obvious and you will be much more confident in your diagnosis:

1.

The size of the heart is slightly

increased compared to the old film.

2.

The pulmonary vessels are slightly

increased in diameter indicating increased pulmonary pressure.

3.

There are subtle interstitial

markings as a result of interstitial edema.

4.

There is pleural fluid bilaterally.

Notice that the inferior border of the lower lobes has changed in position.

All these findings indicate the

presence of heart failure.

Silhouette sign

This is a very important sign. It enables us to find subtle pathology and to locate it within the chest.The loss of the normal silhouette of a structure is called the silhouette sign.

Here an example to explain the silhouette sign:

The heart is located anteriorly in the chest and it is bordered by the lingula of the left lung.

The difference in density between the heart and the air in the lung enables us to see the silhouette of the left ventricle.

When there is something in the lingula with the same 'water density' as the heart, the normal silhouette will be lost (blue arrow).

When there is a pneumonia in the left lower lobe, which is located more posteriorly in the chest, the left ventricle will still be bordered by air in the lingula and we will still see the silhouette of the heart (red arrow).

The PA-film shows a silhouette sign of the left heart

border.

Even without looking at the lateral film, we know, that the pathology must be located anteriorly in the left lung.

This was a consolidation due to a pneumonia caused by Sterptococcus pneumoniae.

Even without looking at the lateral film, we know, that the pathology must be located anteriorly in the left lung.

This was a consolidation due to a pneumonia caused by Sterptococcus pneumoniae.

Here we see a consolidation which is located in the left

lower lobe.

There is a normal silhouette of the left heart border.

On this lateral

film there is too much density over the lower part of the spine.There is a normal silhouette of the left heart border.

By only looking at the interfaces of the left and right diaphragm on the lateral film, it is possible to tell on which side the pathology is located.

First study the lateral film.

Then continue.

On a normal lateral chest film the silhouette of the left diaphragm 2- can be seen from posterior up to where it is bordered by the heart, which has the same density (blue arrow).

One should be able to follow the contour of the right diaphragm -1- from posterior all the way to anterior, because it is only bordered by the lung.

Here we cannot follow the contour of the right diaphragm all the way to posterior, which indicates that there is something of water-density in the right lower lobe (red arrow).

On the PA-film there is a normal silhouette of the heart border,

so the pathology is not in the anterior part of the chest, which we already suspected by studying the lateral view.

Why do we still see the silhouette of the right diaphragm on the PA-film?

What we see is actually the highest point of the right diaphragm, which is anterior to the pneumonia in the right lower lobe.

The pneumonia does not border the highest point of the diaphragm.

Hidden

areas

There are some areas that need

special attention, because pathology in these areas can easily be overlooked:

- apical zones

- hilar zones

- retrocardial zone

- zone below the dome of diaphragm

These areas are also known as the

hidden areas.

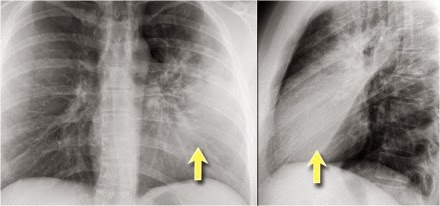

Notice that there is quite some lung volume below the dome

of the diaphragm, which will need your attention (arrow)

Here an example

of a large lesion in the right lower lobe, which is difficult to detect on the PA-film, unless when you give special attention to the hidden areas.

Here a pneumonia which was hidden in the right lower lobe mainly below the level of the dome of the diaphragm (red arrow).

Notice the increase in density on the lateral film in the lower vertebral region.

You may have to enlarge the image to get a better view.

First study the CXR.

Notice the subtle increased density in the area behind the heart that needs special attention (blue arrow).

This was a lower lobe pneumonia.

First study the CXR.

We know that in some cases there is an extra joint in the anterior part of the first rib which may simulate a mass.

However this is also a hidden area where it can be difficult to detect a mass.

In this case a small lung cancer is seen behind the left first rib.

Notice that is is also seen on the lateral view in the retrosternal area.

Continue with the PET-CT.

The PET-CT demonstrates the tumor (arrow) which has already

spread to the bone and liver.

The diagnosis was made by a biopsy of an osteeolytic metastasis in the iliac bone.

First study the

CXRs.The diagnosis was made by a biopsy of an osteeolytic metastasis in the iliac bone.

There is a subtle consolidation in the left lower lobe in the hidden area behind the heart.

Again there is increased density over the lower vertrebral region.

suggested reading